The Paris-Roubaix bike race is often called the Hell of the North since much of its route passes through regions devastated by fighting during the First World War. The name could equally apply to the brutal nature of the ‘parcours’ though – cobbles, mud, farm tracks and broken tarmac are all key components in the annual event. Travelling to northern France to ride the real thing sounded like a great idea in principle, but in practice, it would have been expensive and complicated, so Olly put his route-planning brain into gear and came up with his own closer-to-home version instead.

“Would you like a chair, pet?” said the lady who managed the café. Barry was standing up, leaning on the window sill, with a slightly pained expression on his face. The rest of us were sat in a large circle, a table full of half-finished tea-stop detritus in front of us. The café manager, who it must be said had quite a fierce demeanour, had a chair in one hand. She’d obviously spotted that while the rest of the group were sitting down, Barry was standing and was clearly in some discomfort. “Would you like me to give your shoulders a rub?” she asked. We weren’t entirely sure whether this was a genuine offer, but it turned out that it was and so she sat Barry on a chair in front of her before proceeding to enthusiastically try and remove the knot from his shoulder muscles using the pointy part of her elbow. “My husband works in the forestry industry, so I spend a lot of time doing this for him”, she said, pushing her elbow in so hard that Barry winced in quite an impressive manner.

At this point, we’d covered a little over half of our planned route. Luckily the route was front-loaded with the harder ‘sectors’ – four cobbled climbs, the worst of the muddy sections, a velcro-esque grassy field crossing and several bits with a block headwind had already been dispatched. Despite our total route being less than half the length of the Paris-Roubaix or the Tour of Flanders and with our average speed just nudging over 20kph rather than the 45kph+ that the pro racers manage, we were all starting to feel the toll a little. Fortunately, I’d planned in two café stops (plus I had a backup open-all-hours shop up my sleeve for later in the ride), so we were well-fuelled at least. I hadn’t even considered the possibility of a mid-ride shoulder massage though, so that was an added bonus.

Ten years ago I’d been rash enough to organise the inaugural Hell of the North (East). The anniversary seemed an auspicious time to organise a re-run, except that this time I’d be riding with a group of friends (rather than the public) and instead of riding a hotch-potch mix of road bikes, touring bikes and cyclocross bikes, this time we would all be on gravel bikes, which meant I could make the route more challenging (and even more fun).

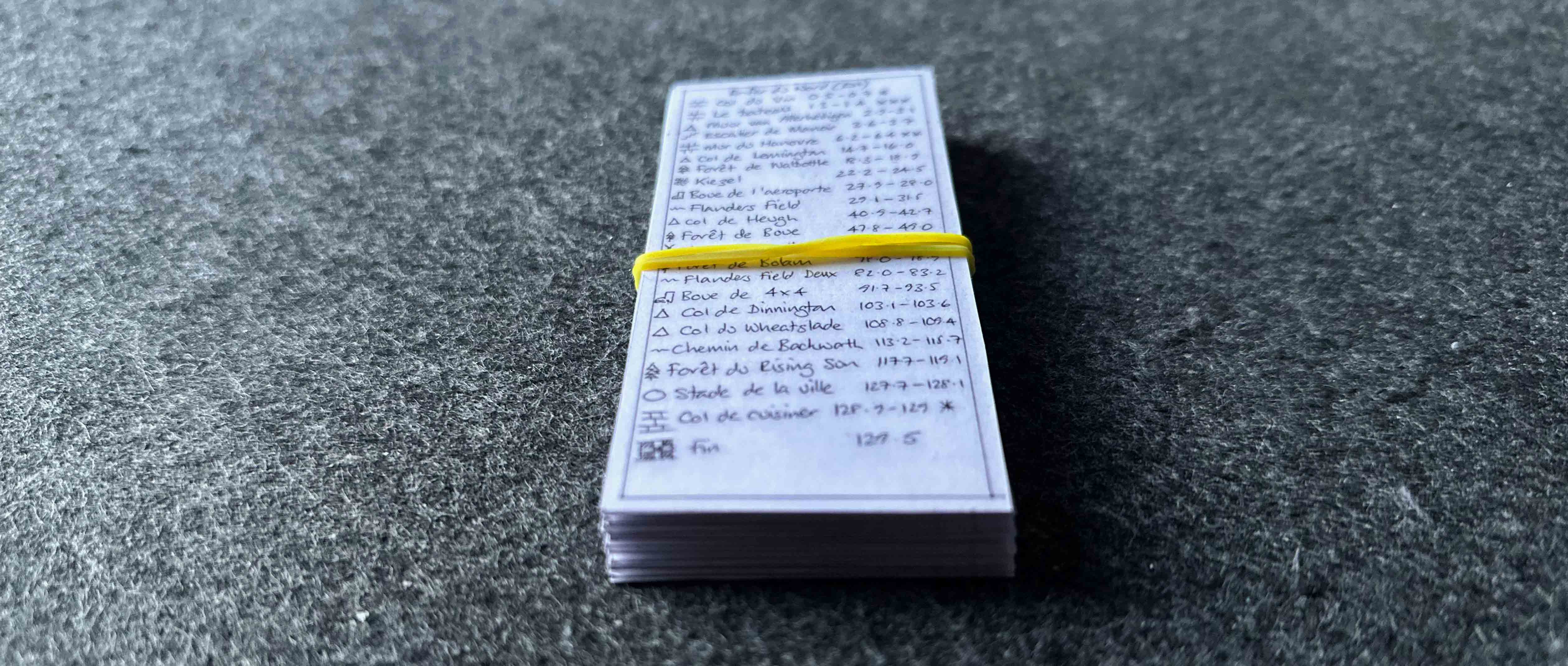

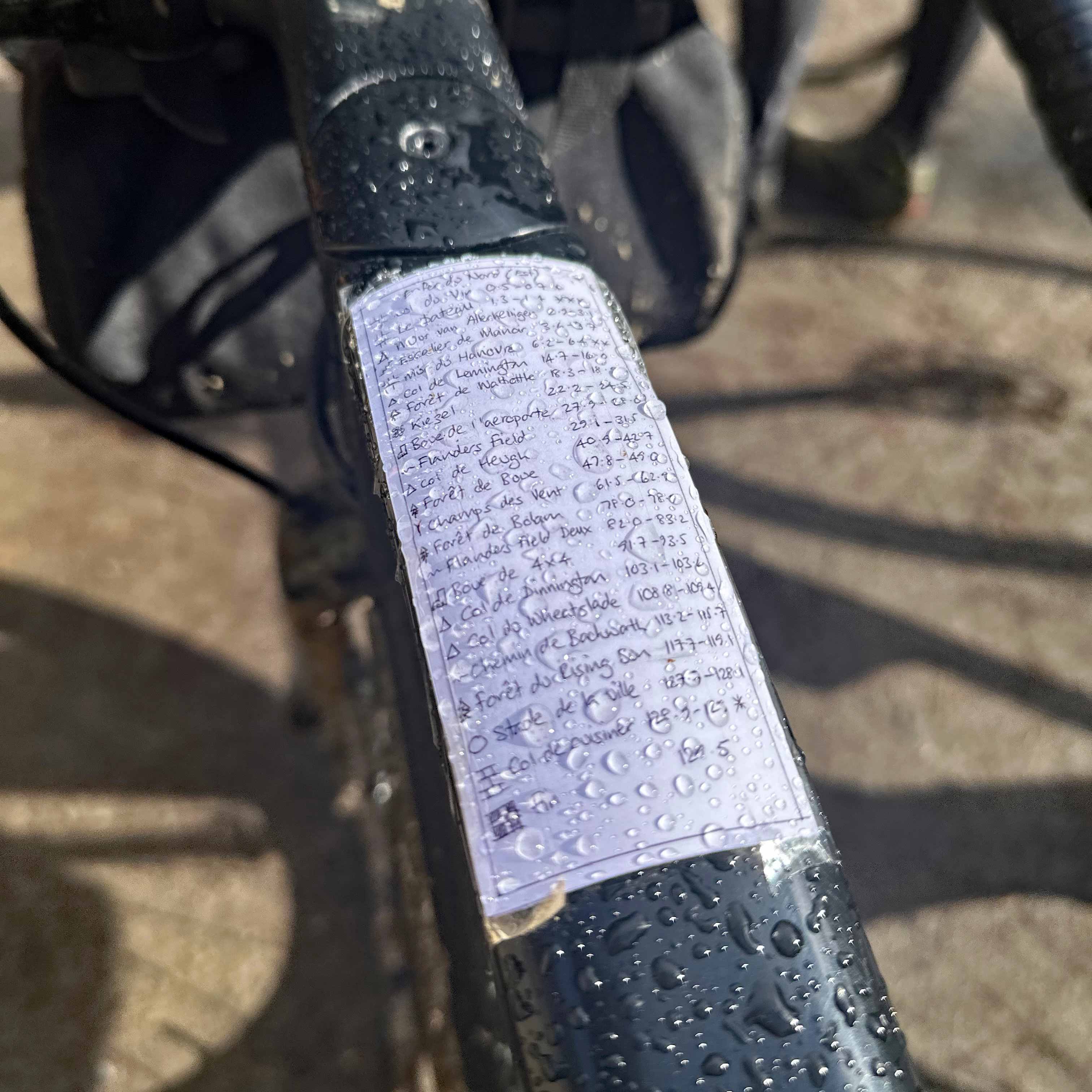

My idea was to take elements from both the Paris-Roubaix (pavé, farm tracks, grotty post-industrial bits, broken tarmac and, most critically, a velodrome finish), but blend in elements of the Tour of Flanders too (cobbled ‘helligen’, block headwinds and Belgian beer) to create a homage. I spent way too long pouring over digital maps and scouring the recesses of my brain for half-forgotten sections of trail that I could meld together to form the finished route. Once I’d identified the potential sectors, each one was translated into either schoolboy French or Flemish (apologies to any foreign-language scholars for my blatant bastardisation of your languages) to give them an appropriate name. The jagged cobbles of Dog Bank where the route climbed past the All Saints Church soon became the Muur van Allerheiligen, the stepped ascent close to Manors metro station became Escalier de Manoir and the wind-battered grassy bridleway near the Ryals became the Champs des Vent. With the sectors identified, it was a simple case of digging out my favourite pen and producing some laminated stem stickers. This might seem pretty pointless in the era of digital mapping and GPS units, but was a suitable hat-tip to the inspiration for the route and gave us all a good memento of the day.

In my (slightly biased?) view, part of the requirement of a good route is to show the riders something (or somewhere) that they might not have seen before. If you can pull this off with a group of riders who have lived (and ridden) in the area for decades, then there’s a big sense of satisfaction. I heard a couple of “Oooh, I didn’t know this bit existed” type comments within ten minutes of us setting off, which was the perfect start to the ride! The first part of the route headed through the Ouseburn, at one time the industrial heart of central Newcastle. Short steep cobbled climbs were interspersed with sections of tarmac and bike path, our route climbing steeply up above the valley before descending straight back down to the River Tyne.

No sooner had we reached the river again, than my route climbed straight up the janky cobbles of Dog Bank and passed the All Saints church. Perhaps not quite as iconic as the chapel at the summit of the infamous Muur van Geraardsbergen in the Tour of Flanders, but with a crystal-clear blue sky backdrop and lit up by the early morning sunshine, it wasn’t too shabby a pastiche.

I had promised the riders a bit of a magical mystery tour through the heart of central Newcastle. While a long flight of steps, graffitied 1960s concrete walkways and anti-motorbike barrier chicanes aren’t typically found in the Spring Classic events that you watch on the TV, they did make for entertaining riding. Fortunately, despite us having chosen the Good Friday bank holiday to undertake our ride, we were out early enough to beat the crowds and had the first part of the route to ourselves. We made up for the lack of spectator-created atmosphere with the sound of our freehubs reverberating off the concrete walls.

After a rapid plummet down the cobbled surface of the ancient Side, we arrived back at the river for the second time. Being a dastardly route planner, my next challenge was a sector I called the Mur du Hanovre, a 300m long cobbled climb which took us up past former industrial buildings and spat us out at the back of Newcastle’s Central Railway Station. The climb averaged around eight percent, which sounds like it should have been a breeze, but the cobbles are wide-set and slicked with moss, making them a suitable challenge for our Hell of the North (East) ride. Finally, the route turned tail and headed back to the river for the third time. With a measly eight km covered, we had already tackled three “helligen”, ticked off nearly a quarter of the total sectors and most importantly, everyone seemed to be enjoying themselves.

As we rolled along the riverside route of town, John mentioned that his shifting wasn’t as crisp as he’d hoped and he thought that his cassette might have worked loose (blame the pavé?), so we diverted slightly in the hope that The Workshop, owned by the ever-cheerful and hardworking Mario, would be open. Fortunately, even though it was a bank holiday, Mario and Lucas were hard at work, but they managed to find some spare time to fix John’s errant cassette while we waited.

As we left the light industry and residential suburbs of western Newcastle behind, my route took us into a steadily more rural landscape. We ticked off the Col de Lemington, Forêt de Walbottle and Boue de l’aeroporte sectors in short succession. The perpetually wet trail close to the airport sadly lived up to its reputation, with one of the deep-set ruts creating our only accident of the day – that will teach me to try and ride one-handed while shooting photographs on a piece of muddy singletrack! Luckily, I picked a soft patch to land in and no damage was done to rider or bike.

Unlike the pros, who get handed a feed bag while they ride at 30 kph, we decided to do things in a slightly more relaxed manner and stopped for lunch in the tiny village of Matfen. The village shop and café offer an incredibly warm welcome to cyclists, no matter how wet and muddy you are. I suspect the payback is that we probably help provide a significant proportion of their income. With some early spring sunshine continuing to make an appearance, the courtyard tables proved to be a popular choice with most of the road cyclists visiting that day, which meant we easily found space inside for our mud-splattered group.

With lunch digested, we had a diary appointment with some wind. Fortunately it was the turbine variety, rather than the digestive type though. The trail up to the turbines proved to be one of the toughest of the day. It’s a bridleway which crosses two sheep-grazed fields. For a few months in high summer, the fields dry out and become bone-shudderingly hard-packed, but for the rest of the year, they alternate between velcro-grass, Teflon and semi-swamp. None of those choices are particularly appealing, but the views are great and fast-rolling gravel trail afterwards makes up for the energy burned on the field section.

A mix of potholed tarmac, vehicle-width gravel track and some forestry trails saw us arriving at our second café stop at Bolam Lake, home to the pointy-elbowed manager. You might think that two café stops in a ride of ‘only’ 130 km is a bit over-indulgent, but café stops are sometimes more psychological than physiological. The chance to top up water bottles, stretch weary muscles and relax for a few minutes was also something not to underestimate the importance of.

It turned out that our second stop was serendipitously timed too. The weather forecast had predicted clouds would boil up in the early afternoon as our route turned slowly towards the north-east after lunch. Sure enough, right on cue, large ominous-looking clouds began to build. As we sat in the café, a storm arrived overhead and an intense spell of rain made its unwelcome presence felt. A rainstorm when you’re sitting inside a warm café, filling your belly with tea and cake never feels quite as bad as one that arrives when you’re riding across some desolate moorland with no shelter in sight though does it!

With the ground already saturated after months of wet weather over the preceding few months, by the time we came out of the café, the roads were awash. Fortunately, an ever-strengthening tailwind pushed the clouds in front of us, some spectacular storm light bathed everything in an ethereal glow and the sunshine created one of the best rainbows I’ve ever witnessed.

After just over 20 km of minor roads, the final section of the route saw us take to the vast network of former industrial railway lines (now converted into shared-use gravel trails) which envelop the north of Newcastle. I’d deliberately included the “climbs” to the summits of the former collieries at Weetslade and Rising Sun. I use the word climb in the loosest sense of the term, as the Weetslade climb only gains 20 vertical metres and Rising Sun version is even less statuesque with only 16 metres of vertical ascent. The former feels significantly harder than its stats would suggest though and is a sufficiently hard workout, particularly as we already had more than 120 km of mainly away-from-the-road riding in our legs by the time we reached it.

With the sun about to dip into a sea of late afternoon cloud, I suggested a quick team photo at the ‘summit’ of the Rising Sun climb. We were slightly depleted in numbers by this point with two riders having already called it a day, but our spirits were still high and a race-pace blast along the definitely-nothing-like-a-spring-classic section of off-camber, greasy, root-infested singletrack that can be found in the scrubby woodland on the edge of the Rising Sun park soon generated enough endorphins to power us towards the of the end of our circuit.

Our penultimate goal for the ride was the former City Stadium park on the northern edge of the Ouseburn. The gravel running track was the closest thing I could find to Roubaix’s amazing concrete velodrome. While the real thing probably offers slightly less of a challenge in terms of puddles, mud-filled-ruts and dog poo avoidance, the grass-covered banks of the City Stadium do offer the vague feel of a velodrome. The surprised looks of the students kicking a football around on the swampy grass in the centre as we rode the traditional 1.5 laps that the pros race at the end of the Paris-Roubaix also gave us a slight sensation of emulating our heroes in northern France.

With a final swoop, we descended (slightly gingerly given the wet conditions) back onto the ancient cobbles of the Ouseburn Valley on onto our final sector – the infamous cobbled ‘berg’ known as the Col de Cuisine, named after the celebrated Cookhouse restaurant which lies at its foot. With a gradient of around 10% and a total length of 100m, this is hardly the Koppenberg or the Paterberg , but it’s quite hard enough at the end of a long day on the bike!

Finally, all that was required was a well-earned beer to finish the ride and the incredibly hospitable staff at the Brinkburn Brewery made us feel very welcome, despite the fact they were super busy and we were definitely not their usual Friday night clientele. Again, with timing fit for champions of the pavé, an intense downpour of rain started just as we arrived at the pub and finished just before we left.

With bellies full of delicious Belgian beer, faces speckled with Newcastle’s finest Belgian suntan and legs full of pseudo-Flemish ‘helligen’, we definitely felt like we had got our money’s worth out of our Enfer du Nord (Est).

See you in another ten years for a re-run?

If you fancy trying out Olly’s route a little sooner, you can find all the details here: