Trying to eke out the summer gravel riding season as long as possible, Timo Rokitta and partner Mandy Rodriguez pack up their bikes and head for a network of former Spanish railway lines, now converted into use by cyclists and walkers and known as Vias Verdes. If Timo’s story doesn’t inspire you to instantly head to Spain in search of some end-of-season sunshine, we don’t know what will!

After spending the past two years crossing Spain on the old railway bike paths, this year we planned to explore the south of the Iberian Peninsula, specifically Andalusia, with our gravel bikes. Naturally, there are plenty of Vias Verdes trails here as well, allowing us to ride away from civilisation. We chose the city of Murcia as both the starting and finishing point of our journey.

On the outskirts of Murcia, we quickly found the start of the first railway bike path, the Vias Verde de Noroeste. The former railway line between Murcia and Caravaca de la Cruz was built in 1931. It originated at the Murcia Zaraiche station, which can be found as a renovated building at Plaza Circular. The railway line was shut down in 1971.

The first part of the Vias Verde leads through a dry, barren landscape, the “Badlands” of Murcia. The track is partly rough gravel and sometimes sandy. The old railway bridges span dried-out riverbeds (Ramblas) and stretch through vast lime plantations. The highest point is reached at the small town of Bullas and from there it’s a gentle descent to Caravaca de la Cruz.

Jerusalem, Rome, Santiago, Santo Toribio de Liébana, and Caravaca de la Cruz all have one thing in common - every seven years, they celebrate the "Holy Year" in these locations. And 2024 is a holy year. But how did Caravaca earn this distinction? In the Basílica de la Vera Cruz, situated on a hill above the town within a former Moorish palace, a fragment of the cross of Jesus Christ is preserved in a magnificent reliquary. How this wooden fragment came to Caravaca and gave the town the name "de la Cruz" (of the Cross) is not entirely clear. One account is a simple story of a bishop from Jerusalem bringing the relic in 1231. Another legend speaks of two angels assisting a clergyman with the fragment of the cross to convert a Moorish king.

Naturally, after arriving, we visited the basilica to marvel at the cross, which is closely guarded by security. From Caravaca de la Cruz, the track continues gently uphill into the Altiplano of Caravaca. We ride along wide gravel paths, cross a dry riverbed and enjoy the paths at an altitude of over 1,000 meters. Here, the late summer heat is still bearable and the wind provides a welcome cool breeze. We travel for hours without seeing a soul. In the distance, we spot two large flocks of sheep, trailing massive dust clouds behind them in the dried-out landscape. By late afternoon, we find a lovely accommodation in a typical cave dwelling (Cueva) in Huesca. Despite outside temperatures of well over 30°C, it’s pleasantly cool inside even without air conditioning.

After passing several reservoirs, we follow the "Transandalus" trail into the Sierra de Cazorla. The lower part of the ascent is on a wide gravel track, which is easy to ride. But at the end of the reservoir, things get adventurous. A narrow single track winds steeply upward, requiring some pushing. As we continue, we ascend on a bumpy forest path until we reach a clearing. The gradients here never drop below 10 percent. After the descent, we face another challenge at a junction of several paths. Either you ride swiftly through the cool water, or you balance across a wobbly and narrow bridge. I choose the bridge, which in hindsight wasn’t any less strenuous. From there, the route follows gravel paths and broad forest roads toward Cazorla. Only the final descent is paved, which is well-deserved after this grueling stage.

From Cazorla, it's a long descent until just before Ubeda. The picturesque town sits atop a hill, surrounded by Andalusia’s extensive olive groves. We quickly find the entry point to the Vias Verde del Renacimiento. Since there are no signposts for the trail, it’s nearly impossible to find without a GPS device. This section of the Vias Verde Renacimiento is in its original state. Olive farmers use it to access their plantations. After initial excitement, our progress gradually slows down.

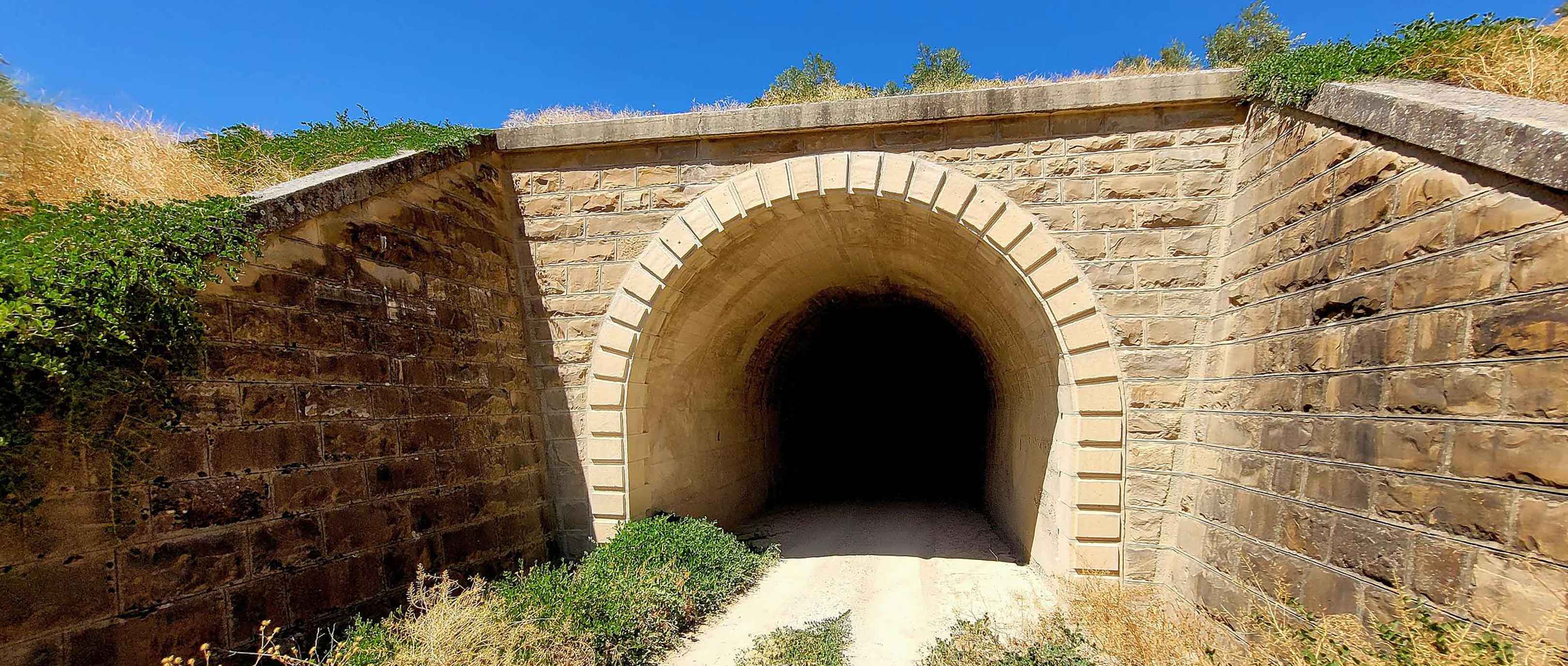

The old tunnels are generally unlit and very bumpy. In one tunnel, we unexpectedly come across a huge, meter-deep puddle. We have to bypass the tunnel with a steep climb through the olive groves. The old bridges also appear more or less in danger of collapsing, giving us an uneasy feeling as we cross them. We don't encounter anyone for miles – this is definitely the outback of Andalusia.

After about 30 kilometers, we reach the developed section of the Vias Verde. We start to enjoy the ride again as we head towards Linares, where we treat ourselves to a large ice cream to cool down after this exhausting gravel ride.

The climb to the pilgrimage church Virgen de la Cabeza takes us through the Sierra de Andujar National Park. Several large signs warn us about the Iberian lynx, which makes its home here. This species is the rarest wildcat in the world. After the viewpoint Mirador Mingorramos, Komoot suggests a remote route to Cardeña. Initially, we cruise along white gravel paths through a typical southern Spanish landscape. We pass several gates and suddenly find ourselves in the middle of nowhere. More and more deer and stags cross our path, which is now extremely washed out. We descend deeper into a gorge, seeing no signs of tyre tracks or other traces of civilisation.

At the lowest point, our GPS units indicate that we should cross a river. However, we find no bridge and instead push our bikes through the dried-out riverbed. Now, the final climb of the day awaits. According to my GPS, it's 6 kilometers uphill with 450 meters of elevation gain. In 38-degree heat and 15% gravel ramps, this is a real challenge. To make matters worse, the gravel is covered with a fine layer of sand, causing my rear wheel to slip whenever I try to stand up. Finally, after reaching the top, we look forward to a coffee break in Cardeña. But suddenly, we are faced with a large iron gate, locked and with no one in sight, just the traces of cows or bulls nearby, giving us an uneasy feeling. We quickly remove the luggage from our bikes and lift them over the 1.80-meter-high fence. It's another 5 kilometers on a corrugated metal road to Cardeña, where we soon find a café and reflect on the day's adventure.

After Azuaga, we briefly leave Andalusia and ride a section through the Extremadura region. The Vias Verde Mina Jayona welcomes us with a perfect gravel path. Fine, compacted gravel makes our hearts race with joy. For over 20 kilometers, we ride through oak groves and harvested grain fields. Occasionally, cows stand under the trees, seeking shelter from the sun.

Our next destination is Cazalla de la Sierra, a charming town with whitewashed houses. The area has been inhabited for a long time, likely due to the presence of nearby mines. The Romans called the town Callentum, and it became famous for its vineyards and wines. During the Al-Andalus period, it was called Kazala, or "fortified city," which evolved into its current name. In the 16th and 17th centuries, the town prospered thanks to its wines and spirits, which were exported to Latin America. In 1730, King Philip V made it his summer residence from June to August and in 1916, the town was granted city rights.

We pass through the Sierra de Cazalla and soon find the Vias Verde Sierra de Norte near the Rivera de Huesna. This former mining railway runs through the mountainous region north of Seville. There was never regular passenger traffic on this line, which was closed in 1970. What remains is a "hill of iron" pockmarked with holes and an 18 km-long track, now a bike path through the Sierra Norte de Sevilla Natural Park.

The open-pit mines can be visited, with marked trails leading through the region. The bizarre landscape, scarred by human hands and colored by the metals in the rocks, has its own unique charm. We notice a flock of large birds flying low over a herd of sheep, seemingly waiting for something. Two Spanish cyclists, who are also watching the scene, tell us that these are Spanish vultures, which can have wingspans of up to 3 meters. Thoroughly impressed, we continue uphill through the rugged landscape to the endpoint of the Vias Verde.

After the Sierra Norte de Sevilla, the landscape becomes flatter and the temperatures rise again to over 30 degrees. After nearly 120 kilometers today, we arrive in Ecija, a lovely little town with many historical sights and narrow streets. "City of the Sun, Frying Pan of Andalusia, or City of Towers"—these popular nicknames for Écija offer a glimpse of the town's unique characteristics, which was already known during Roman rule as Astigi.

At the outskirts of Écija, another "gravel highlight" awaits us. The Vias Verde Sierra de la Campiña takes us directly from here to Córdoba. The Vias Verde winds through a remote, deserted area. Since it’s Sunday, we come across a few mountain bikers enjoying a day on the gravel. Unfortunately, there’s no chance to stock up on supplies along the way. The path is partly very rough, requiring constant attention. Towards the end of the route, the gravel becomes very deep and our front wheels threaten to slip out multiple times. Those riding with knobby tires have a clear advantage here.

The last few kilometers take us along the Guadalquivir River and we enjoy the view of Córdoba's imposing silhouette.

It’s still early in the morning when we leave Córdoba via the 2,000-year-old Roman bridge. After just a few kilometers, we reach the first hills, allowing our muscles to warm up for the day. Our first stop, Baena, is about 60 kilometers away with nearly 900 meters of elevation gain. At a small café, we stop to order two bocadillos and two café con leche. The owner, an enthusiastic cyclist himself, treats us to a huge portion of churros with chocolate, which will sit heavily in our stomachs later.

On the outskirts of Baena, we meet the Vias Verde del Aceite, one of the most beautiful Vias Verdes in Spain. It runs through hills covered with hundreds of thousands of olive trees. For some variety, there are old railway bridges made of steel, with the original railroad ties still in place.

The Olive Oil Bike Route was created on the railway line from Jaén to Campo Real. The route was popularly known as "El Tren del Aceite" (the Olive Oil Train), as the trains primarily transported olive oil from the growing regions of Jaén, Córdoba, and Seville to the ports of Cádiz and Málaga. The Vias Verde del Aceite ends rather unremarkably at a sports complex in Jaén. From there, we quickly reach the vibrant city, dominated by a mighty castle. To reach one of the highlights of our trip, we still have to tackle some climbs from Jaén. Through olive groves, we ride over seven categorised climbs until we reach the small village of Pedro Martínez. This little town could just as well be nestled in the mountains of Mexico. At midday, the village seems deserted, with only a few cats dozing in the sun.

In the only small bar, we drink two café con leche for some strength. Then, after the following descent, we see them in front of us—the "Badlands" of Spain—the desert.

The landscape strongly resembles Nevada or California in the USA. Barren mountains and dried-up fields, with only a hint of green where a stream or dried-up riverbed lies.We find accommodations in the middle of nowhere. At the Balneario de Alicún, we can also enjoy the healing properties of the springs and relax. As a highlight, the guides from the Balneario invite us on an evening hike. Along with Gabriel and Charla, we walk across a high plateau, and they tell us about the history of the region, which has been inhabited for about 5,000 years. We explore an old megalithic tomb and enjoy a unique sunset.

The next morning, it’s only a short hop to Villanueva de las Torres. The climb into the barren desert proves to be first wet and then challenging. Upon leaving the village, we cross a small river, followed by a 12% gradient climb on a gravel path.

Once on the plateau, there is complete silence. The gravel paths are a dream and lead us up and down through a surreal desert landscape with gorges and eroded mountains. We decide to take a break in the small village of Gorafe, which turns out to be quite the challenge, as the path back to our route is extremely steep.

Near Baul, we reach the end of the desert. From there, the Vias Verde del Valle del Almanzora takes us downhill to Baza. There’s a particular challenge just after Baza. The track crosses an old railway bridge that looks more than just rickety. After crossing it with a bit of cold sweat, we see that there was a simple path under the bridge that we could have taken instead.On the following straight section, we face a strong headwind, barely managing to go faster than 20 km/h. Only when the Vias Verde descends into the valley can we pick up speed again. The landscape here is varied and offers beautiful views throughout.

After 80 kilometers, the Vias Verde ends and we continue on small paved roads and sandy tracks heading east. Several times, we have to cross a dried-up riverbed, sometimes on foot, as the stones are simply too large.

A special kind of sprint challenge awaits me when we pass a herd of sheep. The accompanying sheepdog leaps over the fence as soon as he sees me and gives chase. I hear the shepherd shouting something in Spanish after him, but the beast keeps getting closer and I have to put out at least 1,000 watts for 30 seconds to shake him off. A dog bite on the calf would have been the last thing I needed just before the end of the tour.

Slowly, our gravel journey comes to an end. Before reaching Murcia, we ride through an extensive agricultural landscape where pomegranates, olives, lemons, oranges and mandarins are grown.

Then, after nearly 1,500 kilometers, we are back at our starting point in Murcia. Over two weeks on the little-known trails of Andalusia's Vias Verdes, we’ve experienced many adventures and explored countless breathtaking parts of this stunning landscape. We’ll definitely be back again.

There's a list of the various Vias Verdes ways here that Timo & Mandy used. You can find out more information about each one from this website

- VV del Noroeste

- VV del Renacimiento

- VV de Segura

- VV de Linares

- VV del Guadiato

- VV Mina la Jayona

- VV de la Sierra Norte

- VV de la Campina

- VV del Aceite

- VV Vale Almazora

- VV dela Sierra de Baza

- VV Olula del Rio

- VV del Quadix-Almendricos

If you would like to follow in Timo & Mandy's tyre tracks, you can find details of their route here: