Riding 1000km through the heart of the Colombian Andes. Climbing more than 22,000m. Dealing with altitudes of more than 3000m and heat up to 40 degrees C. Riding 165km with the former world road racing champion. Any one of those factors taken individually would be pretty tough, but the recent Trans Cordilleras bikepacking event combined all of them into the same event. Jorge Padrones rode in this year’s event and has sent in this fantastic write-up of what it was like.

If you create a mental image in your brain of the Andes in South America, you’re probably thinking about big mountains without any doubt and just crossing them sounds like a big challenge. If on top of that, we add in the crossing of the three different cordilleras that make the Andes in Colombia in a bikepacking stage race of 1000 km with 22,000 meters of climbing, this sounds like something almost impossible. That is Trans Cordilleras, a bikepacking rally crossing the Andes. A journey with a race inside. Adding the bikepacking and self-sufficient requirement to the mix too, as there will be no feed stations nor mechanics along the way.

My Canadian friend Owen took part last year in the event and I have to say I fell in love after seeing the pictures and said to myself ‘I have to go there’ so by mid-last year I started to plan this adventure.

I have previously done many stage races, mainly mountain biking, but this was the first one in which I would have to carry all my belongings during the race and where I would have no outside assistance, making it a mix between a race and a bikepacking trip. It sounded very exciting, but I needed to carefully choose what to bring, as all the added weight would have to be carried on the numerous long climbs.

After a smooth trans-Atlantic journey, we were soon in Paipa where the race would start. We received our welcome packs and safety position systems and got ready to start. The atmosphere was exciting and you could tell the people were nervous. Everyone was chatting about what was to come.

I knew the race was going to be hard, the daily statistics were telling it was going to be that way, but on the first day we had what we could call a reality check that told me it was going to be tougher than we thought. I have done many races, some of them very challenging, even some which were supposed to be the hardest in the world, but even thinking it was going to be hard I could never have imagined how demanding it would actually be!

Our first stage started in Paipa Boyacá on a cold morning with only 2 degrees with a nice, controlled start on tarmac for the first 30 km and then suddenly the race was on. At km 55 we hit the gravel on our first ascent and straight away there were some really steep ramps. Even though this was just the appetiser, on the first descent we noticed the gravel was not going to be smooth but would be bumpy and hard.

The last climb of the day was our of the Chicamocha Canyon, the second-largest canyon in the world. It was a brutal ascent of around 12 km that took us about 3 hours with temperatures around 40 degrees. On our way to the top, a small fridge from a house saved our day with some coke, water ‘de la llave’ (tap water) and homemade panela as carbs. Another rocky and tricky descent then took us to the finish line.

Even if on this first cordillera (mountain range) the vegetation was not quite as stunning as in others still to come, the landscape was still impressive, especially the Chicamocha Canyon. I spent seven hours on the bike - a long day when you take into account the fact that 76 km of the 137 km were on tarmac!

That night, the odds of me finishing this race that had just started were low. Just after the first day, when I took it easy, I was completely destroyed. But, in the back of my mind were all those beautiful and unique landscapes I could see on the stage so I thought to get on the bike the next day and enjoy it as much as I could, without having in mind being competitive in the race.

The second stage looked almost the same as the first - around 140 km with more than 3000 meters of climbing. This time, the climbs were more gradual, but it took me again eight hours to complete the stage. Looking at the results at the end of the stage, I obviously wasn’t riding as slowly as I thought - I was in top 15. As this was my first race of this type, I was learning as the race was developing. On this stage, I tried to identify in advance the places I could stop for food and water, as the course sometimes goes through very remote areas in which you can’t find a shop for many kilometers. It was better to have it planned in advance so that you don’t find yourself without any water on a long stretch of the route.

Hats off to those riders who had a slower pace and arrived each day after the sun was already gone. Day after day I made this same remark because the later you arrived, the less time you had to do all you need to do after finishing, especially eating and recovery. I think they are real heroes. I also was enjoining the stops to buy food and starting to have my favourite local chocolates and biscuits from the local stores.

This second stage also took eight hours, with almost all the course off-road, but it seemed the beauty of the race was helping as we were about to cross the first cordillera.

The early morning start (7 am) was beginning to be a routine. We soon knew the faces and the names and we were starting to chat and to create bonds before the start. Each morning, Diana made us a fantastic Colombian coffee, which we could enjoy before we set off. We shared the same pain and the same beauty day by day that was indirectly moulding us into a group.

Something I learned on these types of events is the perception of the effort/beauty balance is totally personal and has a lot to do with your attitude. One of the friends I made at the event, Santiago, always arrived at the finish line with a big smile and spoke about what a beautiful day he had and how beautiful the course was.

The menu on the third day was very similar with 110 km and 3200 meters ascent, almost all of them through unpaved roads. Again, it was seven hours on the bike and the landscape was getting greener as we were moving west. We could even see snowy peaks on our way. The Andes in Colombia are somehow a strange range of mountains, as even if you are at 3500 meters altitude, you have plenty of vegetation and the temperature is high for that elevation. We experienced more than 25 degrees at 3500 meters, which makes it very enjoyable for cycling, although this year was maybe too hot on some of the climbs.

When we arrived at the finish line every day, we used to eat together with the ones that used to finish in a similar time and this helped a lot as we were sharing the road but also comments and jokes at the end of the day. In the evenings, we had the opportunity to walk around and see the small and nice villages where we were staying. They were the real jewels of the Colombian countryside, infrequently visited by tourists, so sometimes we were an attraction for the local people.

To mark the halfway point of the race, we were going to hit one of the lowest point of the race - almost at sea level in the city of Puerto Berrio, where we crossed the Magdalena River, the most important river in Colombia. 175 km of riding and 2000 meters of elevation took us there. To reach the river we had one of the longest and most beautiful descents I have ever ridden, as we descended from 2500 meters to 200 meters elevation in just 30 km. After that, we had one of the more difficult off-road sections of this race where it took to us more than three hours to cover 50 km of rolling terrain. The temperatures were very hot and humid as we were very at such low altitudes. What made it more difficult was that we wanted to save some energy for the queen stage about to come the next day, which promised more than 4000 meters to climb. The organisation marked the low altitude stage as the “recovery” stage, so this can let us see how mad is this race in which a 175 km stage can be a recovery one!

It was halfway through the race when I started to understand what it was about. It was not about beating anyone else, but about fighting against yourself. It was not about comparing yourself to others, but about building camaraderie and company, sometimes with your supposed rivals. It was not a race, was a trip, but an existential trip with a race embedded into it.

The Queen stage was all you expect a queen stage to be - long, hard, but beautiful, with long stretches of gravel and a lot of climbing - almost 4250 meters of elevation gain, with a big part of it at the end of the stage! This stage included one of the most beautiful climbs that we did in the race. The whole stage was almost ten hours on the bike in which I shared the course and my time with different groups and different people. I will remember how the group led by former Dutch national road race champion Iris Slappendel helped me on the flats, where I suffered the most and made it more enjoyable. It was somehow emotional when crossed the finish line – the queen stage was in the bag and we had only three stages remaining to complete our trip.

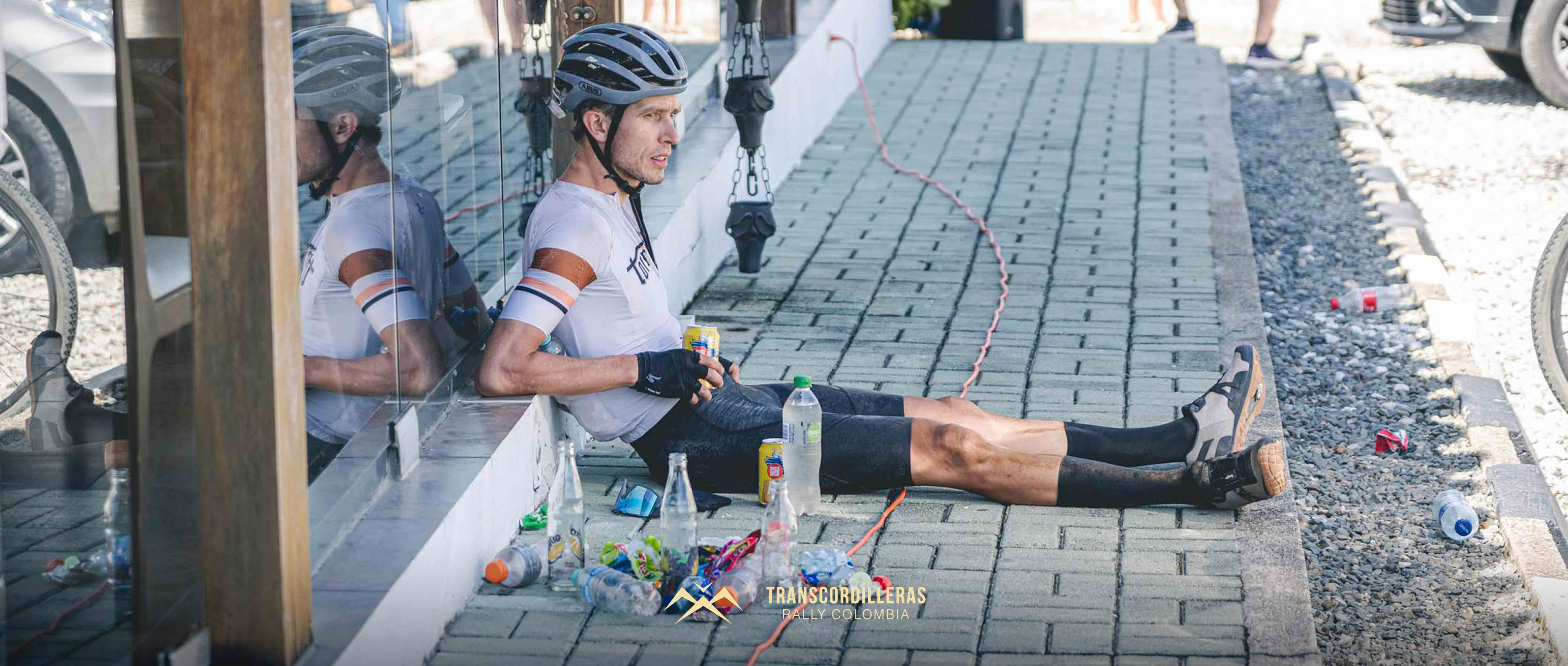

After finishing a stage, the post-race routine begins – first of all finding a car wash to clean the bike, then finding and going to your lodging. Next was having a shower, washing the clothes (I only had one set of kit with me), doing some shopping to carry some food the next day, looking for a restaurant to eat in and finally sleeping as much as you could as we were having early starts every day.

On stage six we were already in Antioquia and ready to cross the last cordillera. All the route had been beautiful, with some of the most beautiful landscapes I got to see, but it was even more special in this area. Stage six was also very special for me as from the start I was sharing the group with one of the world’s best-ever cyclists, Annemiek Van Vleuten. I ended up sharing the whole stage with her and had the opportunity to chat, ask and learn many things along the 165 km stage, which included many long ascents and gravel descents. This was a gift that the race and cycling made for me, but this will be another story.

For stage seven, we started from the beautiful Fredonia, in the area where coffee is grown. We had the shortest stage in the race, just 78 km in length, but it was not that easy with 2000 meters to climb. Even with that, it felt to us like a very short stage and the riders went full gas, even after the long days before. We climbed on a nice gravel road to one of the jewels in this trip, the city of Jerico, famous as a dramatic stage finish in the Tour of Colombia. Given that we all finished early, we shared some time and refreshments in the main square, increasing the sense of community of the event. In the end, we all were sharing one of the most beautiful and exhausting experiences in our lives.

The last stage was meant to be a fun ride shared between all the riders - 120 km of tarmac, a huge road descent at the beginning and some rolling terrain afterwards to take us to the last finish line of the race in Santa Fe de Antioquia. But a ‘fun ride’ could not happen as the race was still on and positions could still change. I enjoyed this last stage as we were in road racing mode with constant attacks and persecutions. I rode in the front group until six of us were away in a breakaway. We even sprinted for the top ten on the stage. It must be strange to see people sprinting on their bikes with all their bike-packing gear!

I have no words to describe the feeling of crossing the finish line. The first one was to hug my fellow riders and I had a feeling of big accomplishment, but with a note of sadness as our beautiful journey came to an end. We crossed the Andes and the three cordilleras that make up Colombia on some of the most difficult gravel roads. We saw some of the most beautiful landscapes on earth just with our bikes, unsupported. Just us and our colleagues riding the same race.

This is an atypical race, hard, beautiful, unsupported, a race within a trip, a trip that every year changes. It has the same essence, crossing the three cordilleras, but there is a different route every year, changing even the direction from east-west to west-east. I think all those particularities make me wish to be able to do another trip through the Colombian Andes next year. To come and once again and fight with giants. Those giant climbs and descents.

In the meantime, the faces of my colleagues and the shared stories with the rest of the participants will be alive in my mind and will keep me dreaming of next year’s trip.

If you would like to see more information about each of the stages of this year’s race, you can find it in Jorge’s komoot collection:

Images courtesy of Trans Cordilleras