If you had to write a list of things you were most worried about when signing up for a bikepacking event, stomach issues, aggressive dogs, acacia thorns, exhaustion and deep sand would likely be some of the highlights, but for riders taking part in the Atlas Mountain Race, they’re par for the course. Despite its super tough reputation, Valerio Stuart had dreamed about taking part for years. Would he manage to banish his demons and make it safely to the finish? Read on to find out…..

I discovered cycling during the second Covid19 lockdown, well in my thirties and relatively late in life. Shortly after, I stumbled upon bikepacking through a YouTube video called Into the Rift, which chronicled the madness of riders tackling the Atlas Mountain Race (AMR) in Morocco.

Three years later, I somehow found myself in Marrakesh, lining up for that very race. The entry list was stacked with some of the biggest names in bikepacking - winners and contenders from all the major ultra-races including Sofiane Sehili, the 2020 AMR winner featured in the documentary film and plenty of up-and-coming talent. As I scrolled through the start list, I couldn’t shake the imposter syndrome.

Was I ready? Could I really finish this? I had never been to Africa, never ridden a race this long and felt out of my depth. One thing I knew from previous editions - many riders wouldn’t make it to the finish (note - the scratch rate from the AMR is approximately 50%). Those who go out too hard often pay the price. My plan was to pace myself and see if the past months of training had paid off. More than anything, I wanted to experience the full route. The adventure ahead was both terrifying and exhilarating.

1300 km, 23000m of climbing and a whole lot of challenges stood between me and the finish line in Essaouira.

Day 1: The start

The peloton rolled out at 6 p.m. under police escort, a mass of riders taking over entire roads of Marrakech, the setting sun casting long shadows. It felt more like the opening of the Tour de France than a bikepacking race. My legs felt good, I was excited, focused and determined to reach Essaouira.

Maybe it was pre-race nerves, or maybe it was the unwise decision to eat my weight in Moroccan sweets earlier that day. Either way, I had to make an emergency pit stop in a nearby field not even 30km into the race. The stomach cramps persisted and I stopped eating, which is capital sin #1 in cycling and ultra-racing. Low fuel leads to slow pace and low mood and I was about to approach the toughest climb of the race.

The first 120 km were a relentless climb, culminating with the Telouet Pass (2,500m). Switchbacks lined with frozen snow drifts wound their way up the mountain. Thankfully, my winter training in the Peak District had prepared me for this. I pushed on, overtaking struggling riders. Some were already scratching due to injuries or mechanicals. Cramps kept stabbing me, my legs were screaming for a break, but I pressed forward.

Once at the summit, all you could see was a long string of headlights snaking down a treacherous mule track. The path often disappeared and I navigated my way forward using tyre marks from the riders ahead. Most of the descent was on a narrow gorge peppered with boulders and ice. I rode short parts of it but with 1,200km to go, it simply felt not worth the risk. Instead, I opted for running using my bike as a crutch, a full-body workout just to keep moving.

Judging the depth of the snow drifts was tricky as it was no more than a thin sprinkle in places and thigh deep in others, covering deep voids in the broken gorge. My technique was far from pretty, but it got me down to Checkpoint 1 just after 5 a.m., right on my schedule.

Day 2: Mechanical nightmare and mental lows

The volunteers at CP1 welcomed riders with warm Moroccan tea and outside, a small shop offered an array of chocolate, biscuits and snacks. Despite my wary stomach, I took the risk and ordered an omelette at the restaurant next-door.

As the first hints of dawn crept over the mountains, the temperature plummeted even further. By the time the sun finally peeked over the horizon, it revealed a stunning landscape: vast, red valleys, dramatic canyons and fast, rocky trails. A few riders ahead of me slowed down, unable to resist the beauty of the moment. Though we were racing, this was too magnificent not to stop for a photo.

The route meandered through quiet villages, their ancient mud-brick structures blending seamlessly into the landscape, a distant call to prayer drifting through the crisp morning air.

My main target for the day was Imassine (258 km), the last real supply point before an arduous 100 km long stretch of remote terrain. The riding was fast and I was eager to make solid progress. Then, an unexpected hiccup: my chain jumped off the chainring. I stopped to put it back on, but not even a minute later, the chain fell off again. Concerned, I pulled over to inspect the bike. Unable to spot any obvious issues, I wiped down the chainring and continued.

The trail dipped into a dry valley, crossing sunbaked riverbeds that required short hike-a-bike sections. In some of these dry riverbeds, small windows and doorways were carved into the rock, with families working nearby - some tending goats, others scavenging for resources in the dusty expanse.

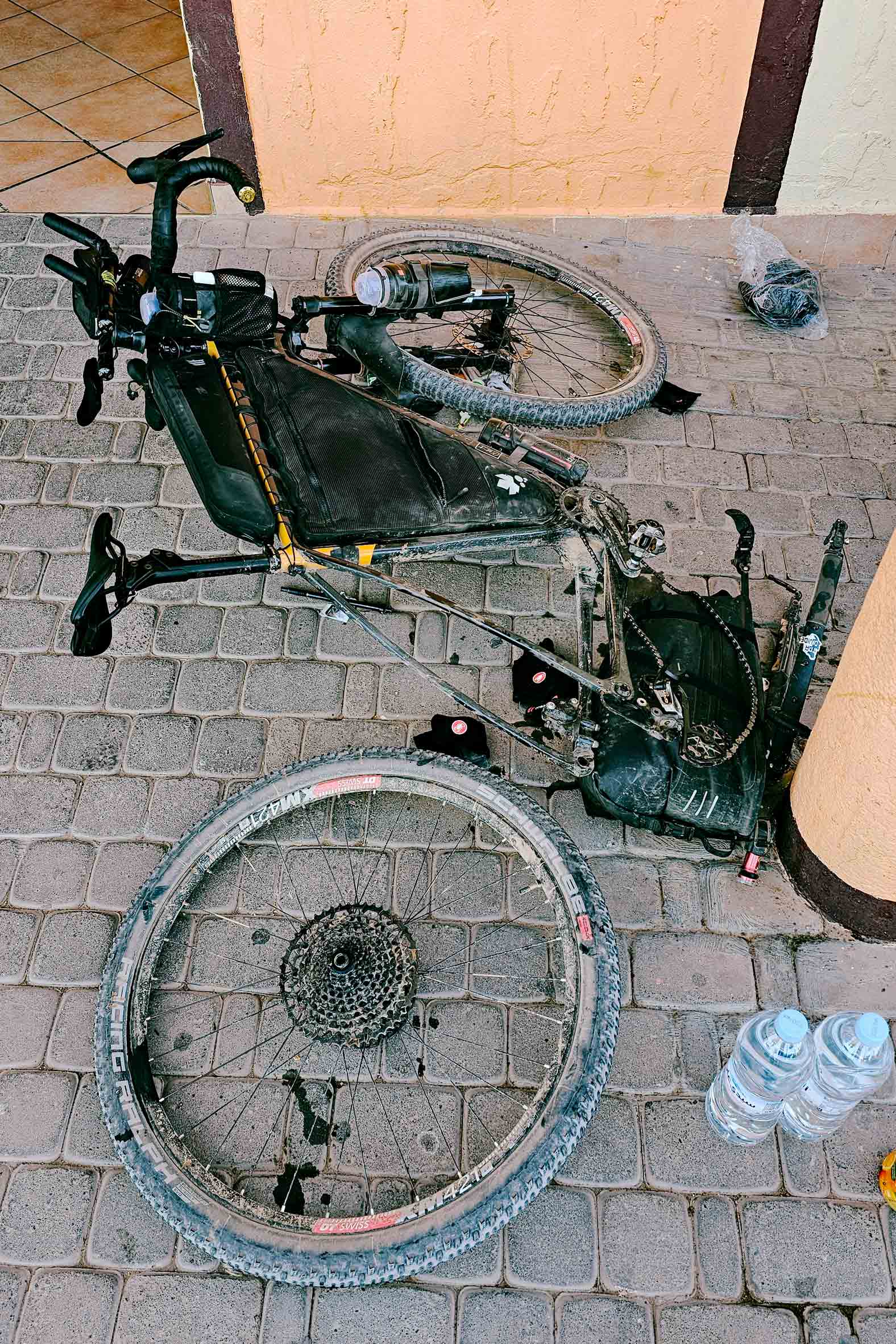

It was while pushing my bike over one of these crossings that I noticed something strange: my pedals were spinning even though I wasn’t turning them. Something seemed to be wrong with my rear hub. I suspected that dirt and sand had jammed the springs in my freehub, causing the cassette to engage even when I wasn’t pedalling. My fears were confirmed when I tried to coast down the next descent, only to have the chain whip forward and fall off again. I had no choice. If I wanted to keep the chain from dropping, I had to keep my legs moving at all times, even on off-road descents. It was absurd and exhausting, but there was nothing else to do except push forward.

I finally stopped at a gas station after Imassine, a few hundred meters off-route. Other riders already at the gas station were scratching and organising their return to Marrakech. I inspected my bike again, hoping to diagnose the issue but nothing obvious stood out. I wasn’t convinced the freehub was the problem, but I had no idea what else it could be. I faced a choice: scratch from a race I had dreamed about for years or ride the remaining 1,000 km as if I were on a fixed-gear bike. The choice was easy.

I put my wheel back on and set off, bracing myself for the next section which included a well-known river crossing. Only that the crossing never seemed to arrive. When I glanced back, I saw another rider. I carried on following the GPS track, perplexed, until I decided to stop and check my location. My heart sank. I was 15 km off-route. The other rider? A scratcher heading back to Marrakech. The realisation hit hard, as I shouted profanities in the air and for a moment, seriously considered quitting. I tried to calm down, angry at myself for the silly mistake and forced myself back on route. Eventually, I passed the gas station again and rejoined the correct route.

The river crossing finally appeared, looking far less dramatic than I had imagined. I took my shoes off and waded through. Night fell and the gravel double tracks ahead seemed to stretch endlessly. Riders began pulling off to sleep, their sleeping bags tucked into rocky outcroppings along the trail. I was mentally wide awake and still physically capable, so I pushed on. By midnight I had ridden 300 km with 6,800 m of climbing - a personal best - but I knew the real challenge lay ahead and forced myself to stop.

The moon hung overhead like a spotlight, so bright that it felt like sleeping under a streetlamp. As I lay in my bivvy, my breathing felt restricted and a sudden sense of claustrophobia set in. I sat up, gasping for air, having some sort of panic attack. It was unexpected, I had bivvied in worse conditions before, but in the heat, dust and exhaustion, my body was rebelling. Eventually, I settled, my mind too fatigued to fight any more.

Day 3: Into the heart of the mountains

At 4 a.m. my alarm woke me from a deep sleep. I wasn’t sure how cold the night had been, but I felt surprisingly refreshed. Pulling on my riding clothes I quickly ate some porridge, preparing myself for another long day, the mechanical issues still in the back of my mind.

The route unfolded onto stunning double tracks through landscapes unlike anything I’d ever seen - scenes reminiscent of North American western films, yet uniquely Moroccan. As the sun broke over the peaks, the valley below erupted in colour - warm hues of ochre, red and deep brown, contrasting with the crisp blue sky above. Mountains with a smooth surface reminded me of chocolate mousse sculpted with a spoon, which prompted me to eat some more chocolate. The trails were fast and wide and every time I turned a corner, my jaw dropped in awe. My chain kept dropping too.

The scenery changed abruptly as the trail became narrow, carved into the hillside overlooking an unexpected lake, a rare sight in these dry Moroccan landscapes. I finally rolled into Afella N’Dra around midday, arriving at a small shop operated by two young children. The younger child, no older than six, clearly ran the show, confidently instructing his older brother on prices.

As I tackled the day's final climb, my largest sprocket began grinding and rubbing unsettlingly. A quick inspection revealed that my b-screw was entirely loose. Any half-decent mechanic would have spotted it sooner, but at least I finally did. Hopefully, my legs could finally rest on future descents. First, though, a gruelling 600-metre climb awaited before I could test the fix.

Ascending along what used to be a gravel road, now noisy with construction transforming it into smooth tarmac, I endured clouds of dust kicked up by passing lorries and SUVs. The harsh sun intensified my fatigue and I felt grateful for my sun sleeves and buff. My Garmin recorded a scorching 36°C on the climb and the dust didn’t help my breathing, with blood already mixing with snot since the previous day.

With about 80 kilometres still ahead to Taznakht (494km), I secured a hotel reservation and cracked on, motivated by visions of a warm shower and comfortable bed. The route snaked through remote, dry valleys dotted sparsely with isolated farms and structures and soon darkness settled.

“There was no heating and only a towel the size of a napkin.”

Alone again under moonlight bright enough to guide my way without lights, fatigue began playing tricks on me. Piles of rocks cast bizarre silhouettes, as I started talking to myself. “Oh there’s a rider in a bivvy” No. It’s a pile of rocks. “What are small children doing here??” Another pile of rocks. “Ah that pile of rocks looks like a goat.” Except the goat was real - dead, stuffed and bizarrely fixed atop a rock, marking what must have been a goat farm. Maybe I really was hallucinating.

Arriving late in Taznakht, the streets lay quiet except for barking dogs and wandering teenagers. The hotel owner awaited my arrival and guided me to my room. There was no heating and only a towel the size of a napkin. Dinner consisted of chocolate bars and a protein shake. The anticipated warm shower disappointed; freezing cold water sent me shivering to bed, huddling beneath blankets with my wet clothes, succumbing finally to sheer exhaustion. Tomorrow, I would ride again.

Day 4 – Onwards to Checkpoint 2

Four hours later, I woke up reluctantly and slid into my damp clothes, shivering slightly as I stepped outside into a sleeping village. Soon after, I ran into Rory, another rider I’d been leapfrogging the previous day. We shared the same surname and now, fittingly, the same hunger for a meal. Checkpoint 2 couldn't come fast enough.

We pedalled away from civilisation and into the wilderness, as dawn slowly brightened the horizon, splashing vibrant hues of red and pink across the sky. The route became a wide, inviting double-track - pure gravel paradise. We traded places frequently until I paused to remove my down jacket, preventing overheating while climbing in the freezing -3°C air. Rory slipped ahead, disappearing into a landscape that felt otherworldly, with rugged sandy canyons stretching endlessly before me.

Then, unexpectedly, the scenery transformed again. I crossed gentle, shallow streams and entered a lush green valley bursting with life. Blooming trees dotted the hillsides and picturesque villages like Aserraregh gazed serenely down from their elevated perches.

Checkpoint 2 (568km) was set in a traditional Moroccan auberge, modest from the outside but beautiful within. The central courtyard welcomed weary riders with intricate tilework, soft rugs and low tables surrounded by cushions. Exactly what my battered body (and butt) needed. Quiet conversations filled the air, riders reflecting on the hardships already endured. The volunteers' table, scattered with abandoned trackers, silently told stories of those who had already succumbed.

Moroccan architecture fascinated me with its mastery of natural ventilation, keeping interiors surprisingly cool despite the midday sun fiercely scorching my skin outside. Imagining life here in peak summer seemed impossible. Leaving Aserraregh, I navigated one of the most beautiful roads I’ve ever seen - a steep descent with hairpin bends dropping into a palmery framed between rugged mountains.

Eventually, I reached a seemingly endless stretch of tarmac. Straight and empty, it cut through a barren landscape bordered only by distant mountains, small scattered trees, and occasional pylons. Music from my earphones distracted me from the boredom, rhythm guiding my pace as I relaxed into my aerobars.

At the village marking the tarmac's end, I hurriedly resupplied before tackling steep, winding streets. Here, stick-wielding children gave an enthusiastic chase uphill. My tired legs struggled to outrun them, until they finally lost interest. The climb grew increasingly rugged, the sun setting and casting mesmerising shadows across the mountains.

I assumed the final 20 km descent to Tagmout (689 km) would be straightforward. I was wildly wrong. Instead, I was forced to negotiate countless dry riverbeds filled with cumbersome boulders, slowing progress and draining morale. Eventually, I reached a tarmac road and was determined to grab a meal in the next village.

After a couple of omelettes at the village shop, I tried to find the strength to push on, just as the shop owner happened to call a friend with a nearby gîte for another couple of riders. It felt like I was stopping too early at this point, but I surrendered to the thought of a warm bed. The other riders and I ended up sharing soup, dates, and tea with the host and his family, chatting despite language barriers thanks to Google Translator. He even followed the race live via its Facebook feed! These moments with locals, rare in the relentless intensity of an ultra-race, reminded me that it wasn’t all about the riding.

Day 5 – The dreaded pop

Unfortunately, my dream of restful sleep turned into a restless night, repeatedly disrupted by riders arriving and chatting loudly. After unsuccessfully fighting for sleep, I surrendered to the inevitable, snoozing until 3 a.m. before reluctantly forcing myself up.

As I departed, Hannes, one of the riders I'd previously met, emerged from the gîte and joined me. We pedalled silently towards the next highlight - the Old Colonial Road. Energised by caffeine and distant flickering red lights ahead, my competitive instinct kicked in. Chasing riders isn’t wise in an ultra, but the temptation proved irresistible.

“I didn't take enough time to assess my footing and as I stepped down, a loose rock shifted beneath me.”

Sadly, darkness concealed the Old Colonial Road’s true grandeur, but moonlight still hinted at the vastness of the landscape around us. It was eerie, empty ````and strangely beautiful. Suddenly, we encountered the road’s first collapse. Think Mam Tor Broken Road in the Peak District, only the road was actually missing here! Hannes was ahead, quick on his feet, dropping into the gap where the road used to be. My bike weighed close to 30 kg and it turned out I'd skipped too many upper-body gym sessions. I didn't take enough time to assess my footing and as I stepped down, a loose rock shifted beneath me. My foot slipped out from under me and before I knew it, I was sliding down, dragged by my heavy bike. Instinctively, I threw out my left arm, trying to grab something, anything, while holding onto the bike with my other arm. That’s when I felt the dreaded pop.

Ah shit, my shoulder.

Embarrassment hit me before the pain did, although it seemed Hannes had not noticed anything. One bruised ass, one bruised ego. I gritted my teeth and reset the joint. This wasn’t my first rodeo. The pain kicked in properly now. I could barely lift my arm, which was fantastic news considering I still needed to scramble up the other side.

I took a moment, then pushed on. The next landslide was just ahead, another chunk of road gone. Hannes charged straight ahead, but something felt off. He was dropping down what looked like a nearly vertical rock wall. I found the actual diversion and scrambled my way across, wincing as my shoulder protested. On the other side, we got back on the bikes, the climb continued and the road grew chunkier.

We reached the summit as dawn broke: the sky was now painted in soft pinks, bleeding into the ochre-hued mountains. I stopped, just for a moment, to take it in - the view, the effort, the madness of it all.

At 9 a.m. we rolled into the village of Issafn (751 km) just as the cafes began stirring to life. My goal for the day was Checkpoint 3 in Tafraout (878 km). While seemingly achievable, I'd learned not to trust such assumptions. Soon after Issafn, I followed possibly my favourite part of the route, especially since I hadn't expected to be wowed again at this point of the race.

The road wound from the bottom of a gorge through remote villages, snaking along a bone-dry riverbed while climbing upward. Kids, barely more than toddlers, wrapped in hand-me-down jackets, stared at me wide-eyed, frozen as if I'd just landed from Mars. Some found the courage to point, calling out to their parents. Women passed by, carrying heavy bundles of wood, covering their faces as I rode past. Men dug trenches, repairing water pipes under the unrelenting sun though there was no water in sight. Life here was harsh, every task a battle against the elements. I couldn't imagine the hardships and I felt incredibly ashamed and privileged to be here, pedalling for adventure while they fought for survival.

Eventually, the remote trail gave way to a wide gravel road busy with trucks and construction vehicles - a jarring contrast after sharing paths mainly with donkeys. The final stretch into Tafraout was breathtaking, steep cliffs, palm trees and, for once, actual water. From the top of the last climb before the checkpoint, I admired the views just as the golden glow of sunset flooded the valley.

Approaching CP3, I transitioned from winding mountain roads to a smooth, palm-lined highway illuminated by streetlights, feeling oddly out of place after days of remote trails. Checkpoint volunteers warmly welcomed me with tales of incredible food and I eagerly ordered a grilled cheese sandwich that fully met my heightened expectations. A vegetable tagine, enormous and piping hot, proved too much for my weary body. As I finished eating, Hannes arrived and we agreed to share a room to rest. I grabbed a shower and finally collapsed into bed, the distant echoes of a Champions League football match playing in the background. Sleep came quickly.

Day 6 – Nearly there

Another day, another dance with the elements. I layered up for the freezing dawn, knowing full well I’d be stripping down by the first climb. Just as the sun rose, the terrain shifted again - steep tarmac ramps, villages perched on rocky hills, the kind of scenery I’d imagined in Spain but was riding through in Morocco. The descents? Absolutely flying. I had no idea if I was actually fast, but I felt fast and that was what mattered.

Rolling into Ait Baha, I found a quiet resupply stop ahead of the infamous 10 miles of sand, which I was about to tackle it in 33 C heat, at the worst time of the day. I reduced my tyre pressure, found the sweet spot and pushed forward, determined to ride as much as possible on my softened tyres. It was like climbing a hill that never ended, except the heat was oppressive and shade non-existent. The novelty of riding on sand ended quickly, I had to get out of this hell.

Finally, tarmac. A village. A much-needed water stop. That was where I met Sandro, both of us collapsing onto the pavement, two grown men wearing lycra and covered in dust, much to the amusement of a group of local girls trying to chat in broken English. Refuelled and slightly less delirious, I set off again, aiming for the Amskroud petrol station before the final push. Just 230 km to go. The hardest parts were behind me. My body and bike were still intact. What could go wrong? Experience should have taught me better.

My plan was simple: cross the next big climb, drop into Paradise Valley and roll into one of the restaurants first thing. But I hadn’t accounted for the bonus climbs - steep, unexpected and unwelcome. Dogs barked somewhere in the dark, probably chasing another rider. The air turned damp, the woods closed in as I pushed on. Eventually, I spotted a flat sandy patch near the top of a climb. It was as good a place as any to crash for the night - high enough to avoid mist, hopefully far enough from dogs.

I passed out half-inside my sleeping bag, warm, exhausted. I was almost there.

Day 7 – And then the punch landed.

I used my last dehydrated meal for breakfast, gathered my gear and started riding into the dawn.

They say everyone has a plan until they're punched in the mouth. So far, I had been pretty much on track with the loose plan I'd formed before the start and I was dreading the moment the punch would land. Was the punch that brutal initial climb? Or the Old Colonial Road, with its hidden dangers? I kept my guard up, wary and restless.

I dropped into a dim valley and soon reunited with Hannes. We knew all too well that the Paradise Valley shops wouldn’t be opening anytime soon. It was just past 5 a.m. and we were about to tackle the last major climb of the route when an unexpected sight stopped us - a tent pitched beside a small roadside fire.

At first, I wondered if one of the participants had decided on a luxurious camping setup. But as we approached, we saw a chair, stacks of water and chocolate bars neatly arranged. It wasn’t a rider at all, it was a local vendor, an angel in a djellaba leaning on a crutch. With welcoming gestures, he invited us to sit down, offering coffee from a steaming pot over the fire. We gladly accepted, relieved it wasn’t a hallucination. The prices were steep by Moroccan standards, but I paid gladly, even tipping, buoyed by this unexpected "trail magic."

This uplifting moment filled me with optimism. Foolishly, perhaps prematurely, I convinced myself the worst was behind me. Big mistake. First came the Moroccan Stelvio. The climb felt endless under the hot sun, but it was manageable. I soon dropped Hannes and began a fast, fun, and flowy desert descent.

And then the punch finally landed.

It had the form of a huge thorn, lodged firmly in my rear tyre. As I inspected the damage, my heart sank - the tyre was completely flat and had de-seated from the rim. Frantically pumping did nothing. Air escaped as fast as it went in. There was nothing that the tubeless sealant could do in this situation. Later, back home from the race, I discovered the thorn had pierced straight through the tyre and even penetrated my tubeless tape. It was a nearly impossible fix trailside. Hannes passed me as I gave up on rescuing the tubeless system and installed an old-fashioned butyl tube. When I finally got moving again, caution dictated my every pedal stroke. I still had 140 km to go and I wasn’t keen on stopping again.

A road descent led me into Imsouane, the ocean now in sight, where a roadside bakery offered much-needed comfort and fuel. The food was excellent, persuading me to pause and enjoy yet another omelette. I reunited with Rory here and over the shared meal, we assessed our finishing time. Essaouira by 10:30 p.m., we estimated.

The next section unfolded gently enough - smooth tarmac gradually giving way to rougher gravel tracks through sleepy coastal villages. With the finish nearly in sight, my excitement grew, making me forget about my tyre mishap and the need to exercise caution. The route transitioned from tarmac to sandy double track to chunky gravel. I started feeling the back tyre squirm beneath me, forcing multiple stops to pump it back up, until I eventually conceded defeat and changed the tube once more.

I reached for one of the expensive Tubolitos that had lived untouched in my repair kit for years. It was finally time to test its worth. Spoiler alert: it failed spectacularly. The tube’s valve refused to thread into place. My frustration grew as I tried everything - my hands, valve-core remover, even pliers - all to no avail. By now, I’d drawn an audience of curious locals on mopeds and even police officers who insisted on helping or transporting me to town. Politely declining their offers, I battled on stubbornly, finally managing to install the second, standard Tubolito. At last, I was back in business.

“I proceeded at a snail's pace, paranoia haunting every metre.”

But my confidence was shattered. I proceeded at a snail's pace, paranoia haunting every metre. Every rock, thorn, and branch on the trail felt like a threat, forcing me into exaggerated avoidance manoeuvres. My earlier hope of finishing in the evening evaporated completely. Past 1 a.m., fatigue overwhelmed me, my eyelids were heavy and my head repeatedly dropped onto my aerobars as sleep tried to claim me. I checked the tracking website - there was no rider behind me. It hardly mattered when I finished now. Spotting a sandy side-trail, I conceded and lay down, setting an alarm for a 30-minute nap.

Waking refreshed I jumped back on the bike, determined to reach Essaouira, especially as I was in desperate need of food. Suddenly, a distant headlight pierced the darkness behind me - I was stunned to realise that another rider was catching up. We exchanged brief greetings, the adrenaline surged and the gloves came off. After nearly 1,300 kilometres, we were about to have a sprint finish!

On the dark roads approaching Essaouira, Michael attacked hard. Forget caution, forget the precious inner tube - this was still a race! My legs screamed in protest, but I chased relentlessly. A pair of stray dogs burst from the shadows, barking aggressively, yet they were too slow to threaten our pace.

There was no time for sentimental reflection on the past few days, no tears for the journey endured. The historic walls of Essaouira were within sight. Despite every ounce of effort, Michael edged ahead, crossing the finish line on Thursday morning just after 2 a.m. About a minute before me.

It was over. I waited for a surge of joy to kick in, for a sense of accomplishment to fill me and lift me up, but I felt nothing. Perhaps it was exhaustion, perhaps disappointment at the slow finish. It didn't matter. Despite every punch thrown my way, I'd finished the Atlas Mountain Race. I grabbed some food and crashed on the floor of a storage room filled with suitcases and bike boxes - ultra-cycling at its finest.

Epilogue

Reflecting on it now with a clearer mind, AMR was everything I had hoped for and more. It was breathtaking, brutal, exhilarating and humbling. It wasn’t the hardest race I've ever done, nor did it scare me or make me feel as alone or vulnerable as other rides had. Perhaps it was because I didn't push myself hard enough physically, or maybe previous experiences had built enough resilience to let the Moroccan dust, boulders and thorns simply wash away, at least figuratively speaking. Perhaps, unknowingly, I had nailed the perfect balance between racing and enjoying the event route.

I didn’t race smart, nor did I chase a top result. But I finished. I had made it, and I had fun. It was over: 1,300 km of tough riding, incredible beauty and everything in between.

Would I recommend it to anyone? I’m not sure, not as a first event.

Would I do it again? In a heartbeat.